Collaborating to problem-solve in cities

Sept. 13, 2018 – In 2010, thanks to incredible teamwork, innovation, and acts of leadership, 33 Chilean miners were rescued after being trapped for 60 days in a cave in the San Jose Mine in Copiapo, Chile.

Eight years later and more than 4,000 miles away, 40 mayors found themselves taking some important lessons from the San Jose Mine.

For Naheed Nenshi, the mayor of Calgary, Canada, the biggest takeaway was that leaders facing problems that seem overwhelming “should not be shy to reach out and ask for help.”

This may seem simple, but it’s easier said than done. For someone like a city mayor, who might be considered a “default” team leader, it can be difficult to relinquish control of a collaborative effort, especially when the stakes are high.

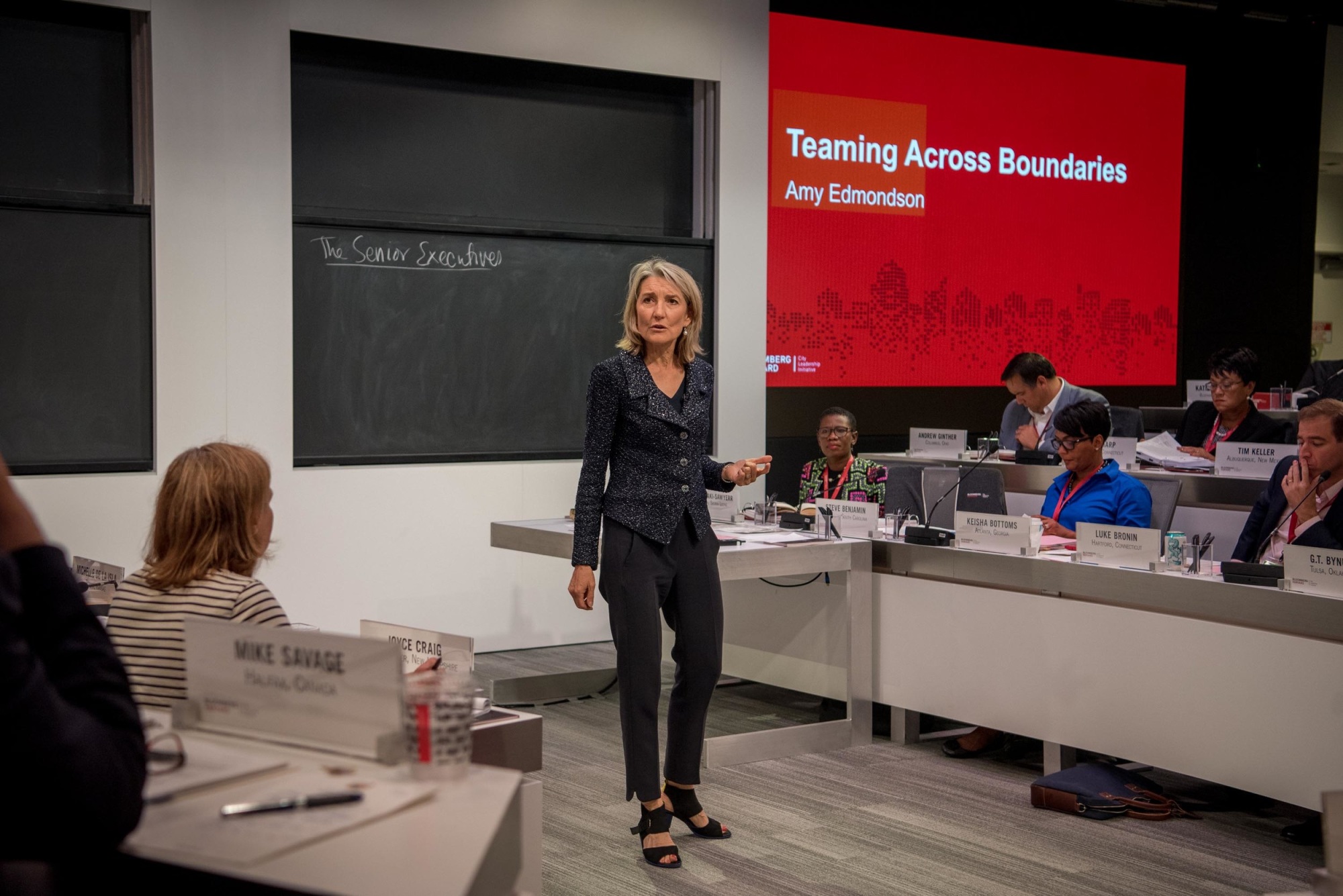

Nenshi, a seven-year mayor of his city, was reminded of this during a discussion on collaboration led by Harvard Business School professor Amy Edmondson during the 2018 mayors convening of the Bloomberg Harvard City Leadership Initiative.

“Sometimes the most important act of leadership is an act of follower-ship,” Edmondson said.

These kinds of leadership decisions are tied to the concept of “teaming,” or the process of collaborating to problem-solve, which is the focus of Edmondson’s work at Harvard.

While a team is a stable entity, Edmondson said, teaming is “teamwork on the fly; coordinating and collaborating across boundaries without the luxury of stable team structures.” She has studied everything from emergency room staff to collaborative animators at Disney, and has found that teaming, when done well, is a very effective way to treat life-threatening conditions, create an animated masterpiece–or rescue a group of Chilean miners.

It’s also applicable to city leaders.

While a mining collapse is a specific scenario, it’s a type of challenge that Edmondson calls a “wicked problem,” or something complex and seemingly insurmountable–the type of challenge that mayors face all the time.

It may truly be impossible to solve these problems alone, but working with the right group of people, and “teaming” effectively, makes it possible.

The most successful teams, based on Edmondson’s research, have some key similarities: clear yet flexible roles for team members; thorough, transparent communication; a willingness to listen to ideas independent of formal power or position; and experimenting and persistence through failure.

Role-definition and delegation are crucial when it comes to leadership of teams seeking to innovate. As Nenshi said, part of this, for a mayor, is recognizing they will not be the best person to lead every team.

Another Canadian mayor, Charlie Clark of Saskatoon, said the importance of communication when teaming really resonated with him. Being direct about goals and expectations, and understanding different points of view, can prevent a collaborative group from duplicating work, from getting confused or frustrated, and from losing valuable time.

Clark had a pretty good idea, going forward, of how he should communicate differently to get city efforts on the right track.

“I’m going to go back and talk to a specific group of leaders in my community,” Clark said. “I want to understand, from their point of view, what the barriers are to collaboration in our city.” In opening channels of communication like this, city leaders can also work to improve a group’s psychological safety–whether members feel comfortable sharing questions, concerns, or mistakes.

Psychological safety is key for collaboration success, Edmondson explained, because it allows all team members to have the most information possible. One team member’s concern, if shared with the rest of the team and addressed, could prevent similar, larger concerns down the line.

This concept ties into another key for successful teaming: a willingness of leadership to listen to ideas from many sources, independent of formal power or position.

Michelle De La Isla, the mayor of Topeka, Kansas, said this is definitely something she is conscious of, as a new mayor forming task forces.

The final piece of teaming that Edmondson touched on, the importance of experimentation and persistence through failure, was also one that De La Isla took to heart.

Solving “wicked problems” requires willingness to try things that might not work, Edmondson said, and willingness to push through and remain hopeful and determined even when some things don’t work.

De La Isla said she has encountered a disillusionment in Topeka with government, and turning this around and getting citizens invested is one of her wicked problems.

“My goal right now is to convince people that government is worthwhile,” she said, “and that they have a say in what government is doing.”